Asterisk (*) indicates required field.

Media error: Format(s) not supported or source(s) not found

Download File: https://www.amdocs.com/sites/default/files/2025-03/amdocs-customer-centric-experience-design_0.mp4 Experience & Digital Engineering Studio

Creating exceptional customer experiences through intuitive design and advanced digital engineering.

Creating exceptional customer experiences through intuitive design and advanced digital engineering.

We uncover the gaps between strategy, technology, and execution to drive real impact.

Our team ensures your digital investments deliver measurable value by aligning business needs, customer expectations, and scalable technology.

The right capabilities. The right time. Real Impact.

Solving the wrong problem costs you time and money.

We help you pinpoint what actually drives growth, efficiency & customer loyalty - then design & engineer solutions that deliver measurable results.

-

Balanced Program Leadership

Ensure successful change implementation by balancing digital maturity with people, processes, platforms, data, and technology, fostering a culture of innovation and adaptability - orchestrating change.

-

Solution Development, Technology Integration, & Optimization

Streamline processes and integrate platforms with cutting-edge tools at the intersection of process optimization, digital transformation, digital engineering, application development management, organizational change, and application modernization services.

-

Innovation & Product Development

Launch new business lines, capitalize with new services/products and enter new markets with customized solutions designed to win in the market and unlock growth.

-

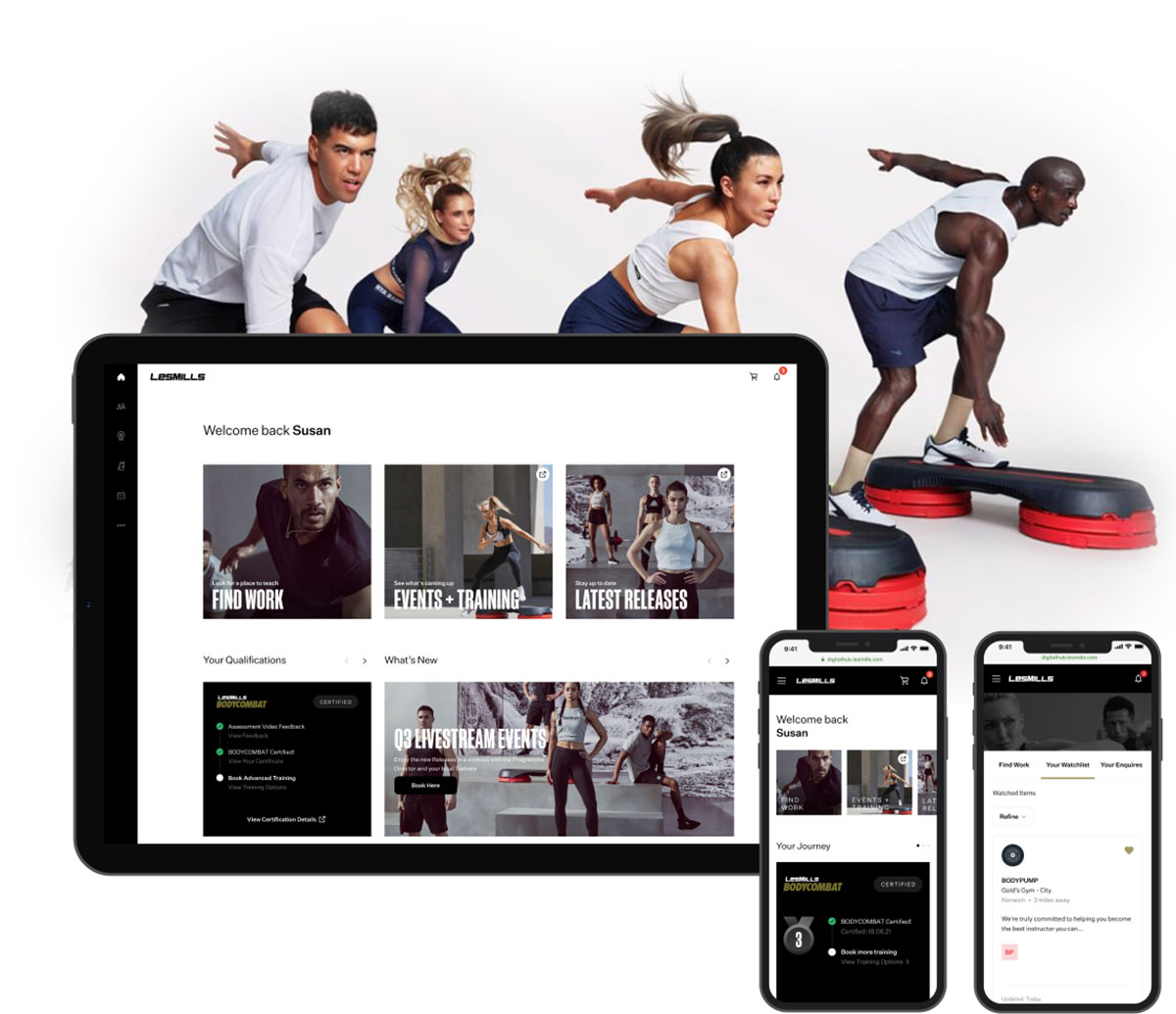

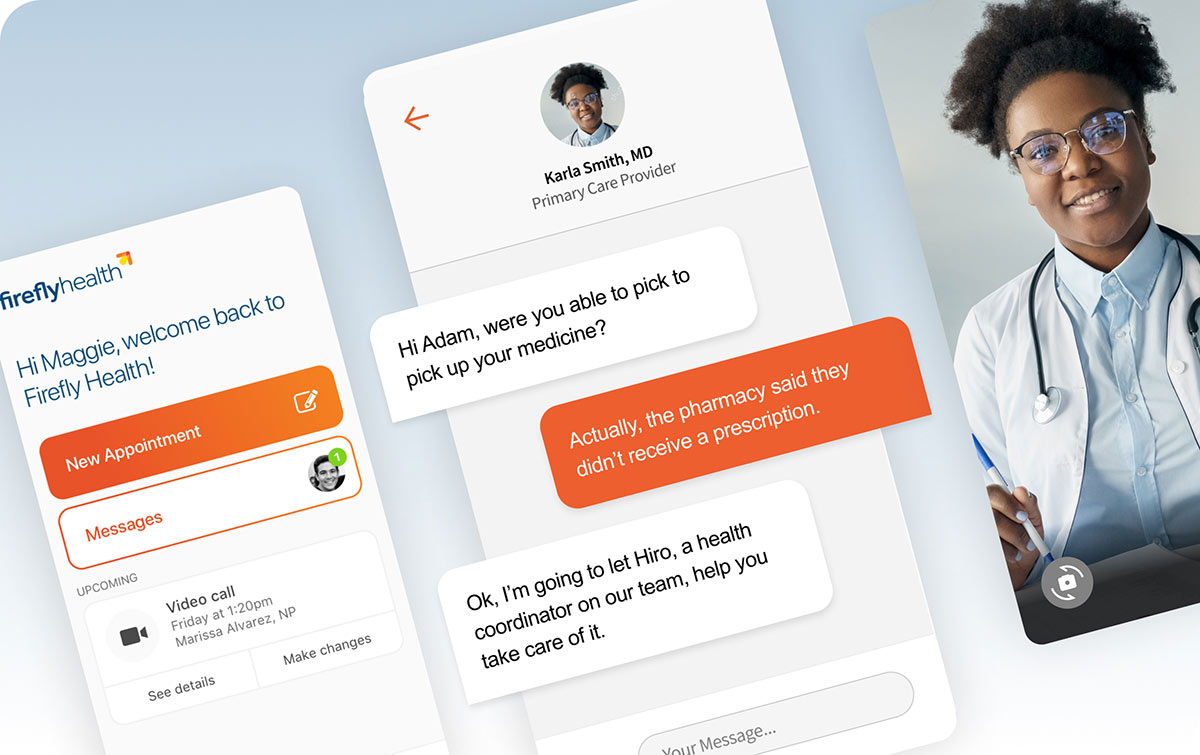

Customer-Centric Experience Design

Develop personalized experiences across all touchpoints to acquire, engage, and retain customers. Elevate customer experiences through unified brand strategy, technology integration, and data-driven insights. Generate differentiation and open new territories for growth.

-

Data Driven Experience & Decision Making

Harness the power of data to orchestrate anticipatory experiences (NBX), make informed business decisions - drive growth, empower teams with smarter tools.

-

Cyber Security & Risk Management

Implement robust security measures to protect data, systems, digital assets and maintain customer trust, leveraging the latest cybersecurity practices.

-

Managed Services & Capabilities Outsourcing

Proactive managed services tailored to optimize operations, boost productivity, and ensure stability with expert 24/7 support.